| World Journal of Nephrology and Urology, ISSN 1927-1239 print, 1927-1247 online, Open Access |

| Article copyright, the authors; Journal compilation copyright, World J Nephrol Urol and Elmer Press Inc |

| Journal website https://wjnu.elmerpub.com |

Case Report

Volume 000, Number 000, January 2026, pages 000-000

A Rare Case of Gluteal Compartment Syndrome and Rhabdomyolysis After Robotic-Assisted Partial Nephrectomy

Alyssa Lombardoa, Daniel Evansa, Hannah Harrisb, Daniel Lib, Julie Bishopb, Eric A. Singera, c

aDivision of Urologic Oncology, The Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center, Columbus, OH, USA

bDepartment of Orthopaedic Surgery, The Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center, Columbus, OH, USA

cCorresponding Author: Eric A. Singer, Division of Urologic Oncology, The Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center, Columbus, OH, USA

Manuscript submitted July 23, 2025, accepted November 11, 2025, published online January 4, 2026

Short title: Compartment Syndrome After Robotic Nephrectomy

doi: https://doi.org/10.14740/wjnu1007

| Abstract | ▴Top |

Gluteal compartment syndrome (GCS) is a rare but serious condition involving high intra-compartmental pressures that can result in rhabdomyolysis with tissue ischemia and necrosis. We present the case of a 38-year-old male with class III obesity who was positioned in lateral decubitus for a 4-h long robotic-assisted partial nephrectomy, completed in standard transperitoneal fashion, for a 3-cm renal mass later diagnosed as renal cell carcinoma, chromophobe type. Postoperatively, patient demonstrated clinical picture consistent with GCS, including pain with passive motion, weakness, tea-colored urine, and elevated creatine kinase (CK). He was managed expeditiously with emergent gluteal fasciotomy. Postoperatively, his CK and pain improved and he was discharged on postoperative day 5. At 1-year follow-up, he has normal renal function, no evidence of renal cell carcinoma (RCC) recurrence, and normal neurologic and muscle function. His case demonstrates the need for a high index of suspicion for musculoskeletal complications when operating on severely obese patients.

Keywords: Compartment syndrome; Gluteal compartment syndrome; Nephrectomy; Rhabdomyolysis; Robotic-assisted

| Introduction | ▴Top |

Acute compartment syndrome (ACS) occurs due to decreased intra-compartmental space or increased intra-compartmental volume in the setting of inherently non-compliant fascia. As the intra-compartmental pressure (ICP) increases, vascular dynamics change beginning with reduced venous outflow and increased venous capillary pressure. In the capillaries, if venous pressure exceeds arterial pressures, arterial inflow is reduced and tissues are exposed to decreased oxygenation, causing ischemia, which can result in necrosis. Rhabdomyolysis causes release of intra-cellular components, which can cause acute renal failure that requires hemodialysis. The incidence of ACS is 7.3 per 100,000 in males and 0.7 per 100,000 in females [1]. ACS most commonly occurs in association with fractures, particularly tibial fractures, but can also occur with other traumas or related to surgical positioning, as described in this case report. Patients with ACS without fracture or trauma are more likely to have delays in diagnosis and experience more complications. Diagnosis of ACS is most common in men younger than 35 years old, which may be related to increased muscle mass and/or association with activities and behaviors resulting in trauma or fracture [1]. Risk factors for clinical rhabdomyolysis in surgical patients, particularly in those undergoing retroperitoneal surgery include younger age, higher body mass index (BMI), and longer operative duration [2].

ACS typically presents within a few hours of the inciting event but can present up to 48 h after. Classically, the presentation of ACS is remembered by “the five P’s” including pain, pulselessness, paresthesia, paralysis, and pallor. However, the timing of these symptoms varies. The earliest objective physical finding is a tense compartment. Subjectively, pain is typically the first described symptom. It is often severe and out of proportion to the exam or may only be present during passive stretching and may be described as a burning or deep ache. In advanced ACS, pain with passive stretching may no longer be present. “Pulselessness” or palpable arterial pulse may not accurately indicate tissue pressures, and pulses may still be present even in severe ACS.

Initial evaluation for suspicion of ACS includes clinical history and examination. Examination should include palpation over the compartment for temperature, tenderness and tension. Passive and active motor functions should be checked. Pulses may be checked by palpation or Doppler ultrasound. Measurement of ICP is not required to make the diagnosis but can aid in cases of uncertainty. ICP can be checked with a manometer, which detects ICP by measuring the resistance of injected saline solution. Another method employs a slit catheter, whereby an arterial line transducer is placed within the compartment, which tends to be more accurate and allows for continuous monitoring. Normal pressures within a compartment are less than 10 mm Hg. ICP greater than 30 mm Hg indicates compartment syndrome and warrants fasciotomy. When the pressure is between 10 and 30 mm Hg, ICP should be monitored serially or continuously, and the delta pressure can be calculated to determine relative under-perfusion. Delta pressure is the difference between diastolic pressure and the ICP; delta pressure greater than or equal to 30 mm Hg is indicative of the need for fasciotomy [1]. Elevated ICP in ACS can result in muscle ischemia and breakdown or rhabdomyolysis, which is marked clinically by elevated creatine kinase (CK) and can result in acute kidney injury requiring dialysis. If there is concern for rhabdomyolysis, renal function tests, chemistry panel, urine myoglobin, and urinalysis should be obtained.

Treatment for ACS is fasciotomy, ideally within 6 h of injury. After 36 h post-injury, irreversible damage may occur, and fasciotomy may not be beneficial but can expose the patient to additional risk [3]. If necrosis occurs before fasciotomy, there is higher likelihood of infection, which can require debridement or amputation to prevent systemic spread or additional complications. After fasciotomy, patients should be monitored for infection, renal failure and rhabdomyolysis. As the edema improves, a skin graft may be considered or required for incision closure.

Gluteal compartment syndrome (GCS) is a rare but serious subset of ACS. Patients with GCS typically have pain with passive range of motion (ROM), especially in hip extension and may have erythema over the hip or buttock. Diagnosis is accomplished clinically, although compartmental pressure measurements may provide confirmation. Treatment involves surgical compartmental release and medical management. We present the case of a 38-year-old male who developed GCS without tissue necrosis or acute renal failure after robotic-assisted partial nephrectomy. We believe this case report to be pertinent to the urologist as lateral decubitus positioning is a common practice and is rarely associated with development of GCS, but early diagnosis is critical to ensuring the best outcomes.

| Case Report | ▴Top |

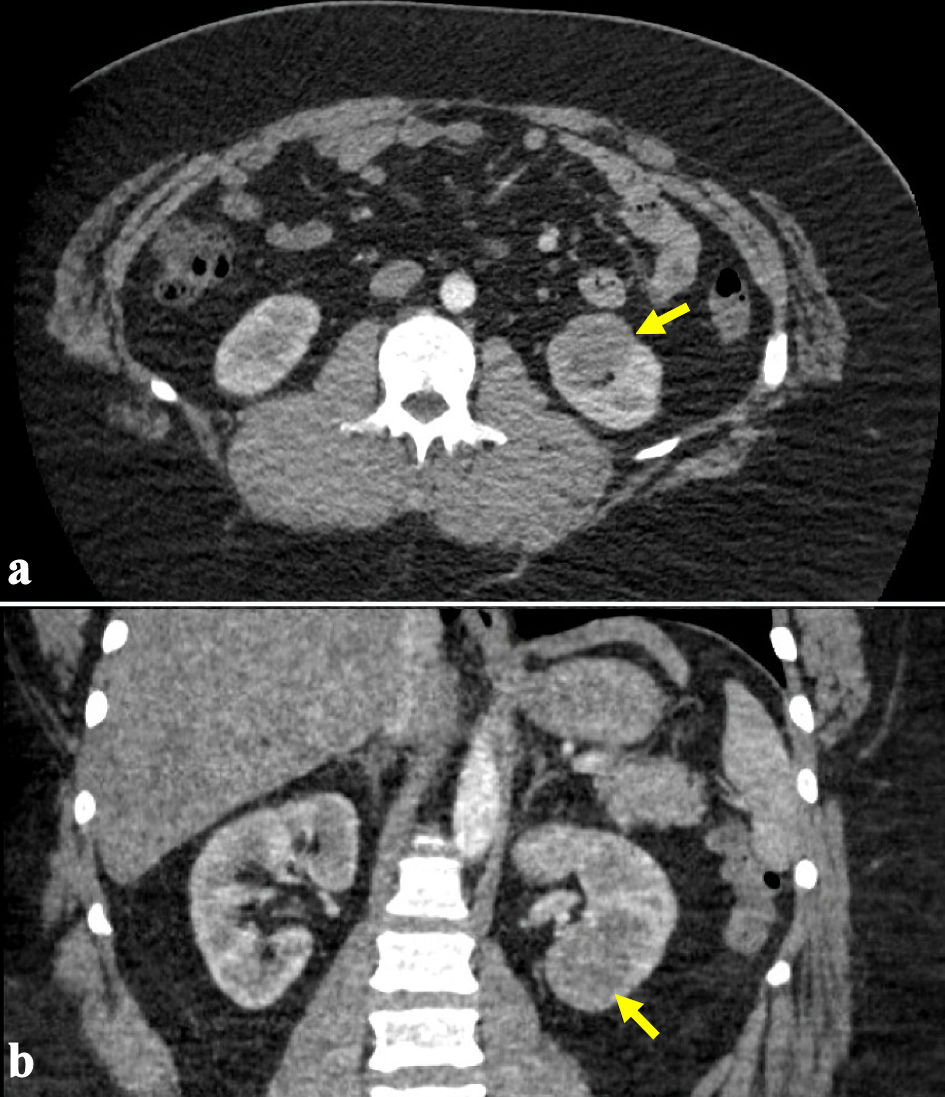

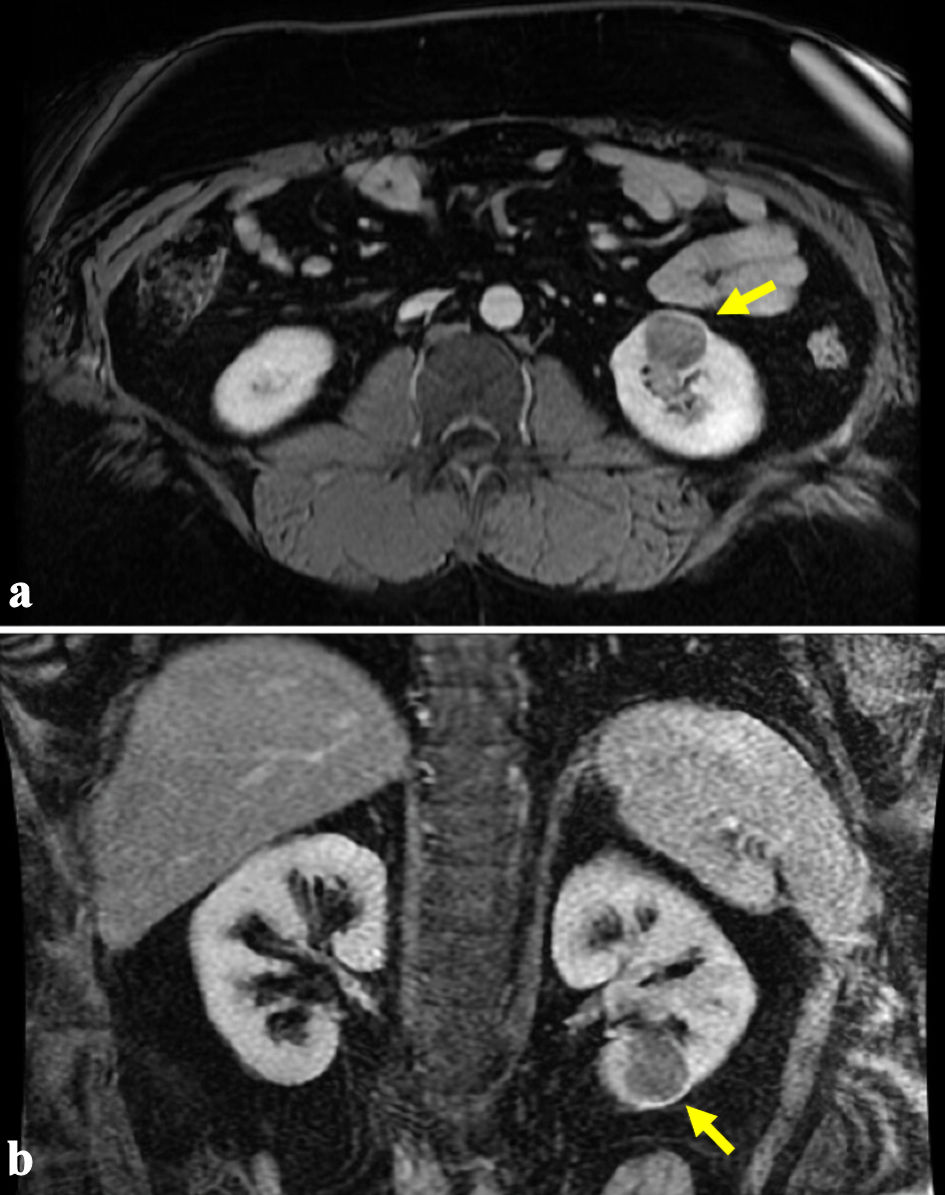

Presentation

The patient is a 38-year-old male referred to our tertiary care center for management of a renal mass. He initially presented to an outside institution with gross hematuria where an office cystoscopy was performed, which was unremarkable. Computed tomography (CT) showed a 3.1-cm soft-tissue density in the lower pole of his left kidney (Fig. 1), and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) confirmed a 2.8 × 2.5 × 2.9 cm enhancing left renal mass (Fig. 2). Notable medical history includes class III obesity with a BMI of 57.9 kg/m2 (Table 1). After thorough counseling on the etiology, evaluation, and management of small renal masses, including increased risk of musculoskeletal complications related to his obesity, the patient selected robotic-assisted partial nephrectomy as his preferred treatment.

Click for large image | Figure 1. (a, b) Representative computed tomography (CT) images demonstrating an enhancing 3.1-cm soft-tissue density in the lower pole of the left kidney as indicated by the arrows. |

Click for large image | Figure 2. (a, b) Representative magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) demonstrating an enhancing 2.8 × 2.5 × 2.9 cm left renal mass as indicated by the arrows. |

Click to view | Table 1. Weight Classification by BMI |

Operative findings

The patient was positioned in the right lateral decubitus position, and the bed was flexed in a jackknife position. The arms and legs were padded, and copious amounts of pillows were used between the legs for pressure injury prevention. The patient was carefully padded with gel rolls behind the back/hips and pads and secured to the operating table with 3-inch silk tape. Ports were placed along the lateral border of the rectus muscle with a supraumbilical assistant port. Surgery proceeded in a standard fashion. Total operative time from skin incision to skin closure was 4 h, warm ischemia time was 41 min, and estimated blood loss was 50 mL. The patient was awakened and transported to the post-anesthesia care unit without immediate concern.

Postoperative course

Upon awakening, the patient complained of severe right-sided hip pain. Physical examination in the post-anesthesia care unit demonstrated soft compartments and no sensory deficits, and he was treated with pain medications and intravenous (IV) hydration. CK measurements were obtained, and his immediate postoperative value was elevated to 24,160 U/L.

Overnight, the pain became more severe, and the patient was re-evaluated, finding worsening pain out of proportion to the physical exam, pain with passive motion, limitation in ROM, and new-onset numbness in the right lower extremity with foot drop. CK level peaked at 29,860 U/L. His urine had become tea colored. Orthopedic surgery was consulted. The diagnosis of compartment syndrome was made based on lab values and physical exam; measurement of compartment pressures was not needed. The decision was made to proceed with emergent gluteal fasciotomy. Release of all three compartments (maximus, medius, and minimus) was performed 17 h after conclusion of the partial nephrectomy. Intraoperatively, his gluteal muscles and the sciatic nerve were noted to be healthy and without ischemic injury.

Postoperatively, his pain and neurological symptoms improved, and he was able to ambulate without a walker or assistance with a gait belt. Serial blood draws demonstrated consistent improvement in his CK levels and absence of acute kidney injury (his preoperative creatinine was 0.85 and peaked at 1.23 as CK peaked). He was discharged on postoperative day 5 from his partial nephrectomy. Since his surgery, he made a full recovery with resolution of pain and maintenance of normal neurological and musculoskeletal function. Surgical pathology demonstrated renal cell carcinoma (RCC), chromophobe type (pT1aNxMx, negative margins). His most recent renal function tests were within normal limits (creatinine 0.96), and surveillance imaging showed no evidence of disease.

| Discussion | ▴Top |

This case demonstrates a unique presentation of compartment syndrome presenting after robotic-assisted partial nephrectomy and in the absence of tissue necrosis or acute kidney injury. GCS is a rare but potentially life-threatening complication after renal surgery, especially those positioned in lateral decubitus position and with elevated BMI. It presents with pain with passive hip flexion, firmness and/or tenderness in the buttocks, and progression to paresthesia and paralysis. Treatment of GCS involves prompt surgical intervention with fasciotomy of the gluteal compartments composed of the gluteus maximus, gluteus medius, gluteus minimus, and tensor fascia lata.

In patients unable to actively participate in examinations, such as patients who remain intubated postoperatively, clinicians should monitor for tachycardia and, in patients at risk for ACS, should conduct physical examination for firm compartments and investigate by checking CK values. Although ICP measurements are not required for diagnosis, in cases of uncertainty, ICP should be obtained with a monometer or slit catheter, with ICP greater than 30 mm Hg being indicative of ACS. Measurement of CK values may also be helpful, as intracellular components are released into the bloodstream during muscle breakdown, elevating serum CK. Elevated CK is indicative of muscle injury but is not diagnostic for ACS [4]. However, elevated CK levels five-fold the normal range are diagnostic for rhabdomyolysis and associated with risk of AKI. Clinical examination of patients with rhabdomyolysis demonstrates muscle weakness, severe pain localized to specific muscle regions and red-to-brown or tea-colored urine. Elevated CK in our patient, together with exam findings, resulted in prompt diagnosis of rhabdomyolysis related to compartment syndrome, allowing for timely orthopedic operative intervention.

In a population-based retrospective cohort study evaluating the incidence and risk factors for postoperative rhabdomyolysis, Gelpi-Hammerschmidt et al reported an incidence of 0.13% [5]. Among the patients who experienced postoperative rhabdomyolysis, there was elevated 90-day mortality, nearly doubled hospital length of stay (LOS) and increased associated healthcare costs. Risk factors included male gender, obesity (BMI > 30 kg/m2), patients undergoing robotic surgery, prolonged operative time (above 5 h), and positioning with use of bumps or pads that can increase localized pressure [4]. Adib et al noted prolonged surgical duration, immobilization, lateral decubitus positioning and obesity as risk factors [6]. Chatzizisis et al reported acute renal failure and need for hemodialysis as one of the more severe sequelae of GCS with rhabdomyolysis, occurring in 10-40% of postoperative rhabdomyolysis cases [7].

In our patient, a key diagnostic component was the development of refractory pain and neurological symptoms in our patient, namely sensory deficit in the patient’s right leg. The patient was also developing a foot drop, related to the common peroneal branch of the sciatic nerve, which can be compressed in GCS. Yang et al reported a case of delayed diagnosis of GCS after robotic partial nephrectomy, in which the onset of lower extremity weakness and numbness was a crucial element in reaching the correct diagnosis [8]. In a systematic review of 139 cases, Adib et al reported that while no difference in permanent neurological function was seen in patients presenting without a neurological deficit, fasciotomies improved outcomes in those who did present with deficits [6]. It is notable that while our patient met all the criteria for GCS with rhabdomyolysis, he never developed acute kidney injury, possibly owing to prompt recognition, hydration, and surgical intervention.

Reports of compartment syndromes in urologic patients are infrequent and most commonly are GCS or “well leg” syndrome, which is a compartment syndrome of the lower extremity. Well Leg compartment syndrome (WLCS) and GCS are most often reported after urologic procedures performed in lithotomy or Trendelenburg positioning [9-11]. In WLCS, the anterior compartment of the leg is the most commonly involved compartment of the four compartments (anterior, deep posterior, lateral and superficial posterior). The tibial, sural, and superficial and deep branches of the peroneal nerve traverse these compartments, and their compression causes deficit in their respective areas. Raza et al described a review of WLCS in urologic patients undergoing radical cystectomy and urethroplasty [9]. In most of these cases, the patients experienced bilateral WLCS after prolonged operating times (> 6 h) in lithotomy or high-lithotomy position. One case report described bilateral GCS in a 61-year-old male with a BMI of 40.2 after a 6-h robotic-assisted prostatectomy in lithotomy and Trendelenburg positions, which was managed with bilateral gluteal compartment fasciotomies [12]. All reports of WLCS or GCS in urologic patients were associated with risk factors including long operative times, obesity, and lithotomy, decubitus, or Trendelenburg positioning; all authors recognized that prompt diagnosis was most critical for optimizing outcomes.

Though GCS is a rare occurrence in urologic patients, urologists should be familiar with presentation and treatment, especially urologists involved in the treatment of kidney cancers, during which surgical intervention is often performed in lateral decubitus positioning with risk of prolonged pressure to the contralateral hip, especially in obese patients. Adiposity is characterized by the presence of increased white adipose tissue (WAT) and stratified by weight in kilograms divided by the square of a person’s height in meters, or the BMI. The terms “overweight” and “obese” are defined by BMI over 25 and over 30, respectively. For the purposes of discussion, Table 1 further classifies obesity by BMI. Our patient had a BMI of nearly 58, putting him in the class III obesity category.

Epidemiological studies have identified adiposity as a risk factor for several medical conditions including type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease, dyslipidemia, fatty liver, and reproductive dysfunction [13]. Increased adipose tissue has been identified as the second most common risk factor for cancer development [13]. A review of over 1,000 epidemiological studies has linked adiposity to several cancers including that of the esophagus, thyroid, breast, liver, gallbladder, pancreas, colon, rectum, ovary, endometrium, prostate, and kidney [13]. Obesity has been identified as one of the most significant lifestyle factors associated with RCC other than smoking and hypertension [14].

However, some analyses have shown that higher BMI is associated with better outcomes and survival in patients with metastatic or advanced RCC with targeted therapy; this phenomenon has been termed the “obesity paradox” [14]. The existence of an “obesity paradox” in RCC is debatable. On one hand, studies evaluating systemic targeted therapies for the treatment of advanced or metastatic RCC (mRCC) show that increased BMI (> 25) was positively associated with progression-free survival (PFS), recurrence-free survival (RFS), cancer-specific mortality (CSM), and overall survival (OS), but these findings are potentially limited to clear cell RCC (ccRCC) and may not applicable to non-ccRCC pathologies [15, 16]. Other studies have argued that in mRCC, elevated BMI is not inherently protective but may appear relatively better than outcomes in patients with low to normal (< 25) BMI [17-19]. Additionally, some authors argue that obesity as measured by BMI is a poor indicator of total body fat and that it fails to account for lean muscle mass [19]. Overall, BMI fails as a metric to consistently predict perioperative and survival outcomes in RCC.

Another perspective aims to understand the possible pathologic and mechanistic role of excess adipose in tumor formation, associated molecular alterations, and subsequent therapeutic response [20]. White adipose tissue (WAT) is not simply storage of excess energy but a dynamic organ populated with adipocytes and immune cells, including B and T lymphocytes, macrophages, and mast cells, which function at the local and systemic levels [13]. In lean individuals (BMI < 25), the WAT is populated with activated macrophages, lymphoid cells, helper T-cells and natural killer (NK) cells, which work with adipose cells to promote anti-inflammatory cytokines [13]. During obesity, adipocytes die of hypertrophy, creating a pro-inflammatory state, referred to as “inflamed WAT,” which is rich with pro-inflammatory cytokines that increase angiogenic factors via cyclooxygenase 2 (COX-2) and prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) production [13]. Sanchez et al investigated the angiogenic and immunologic transcriptomic profiles of the primary tumor and perinephric adipose tissue in normal-weight and obese RCC patients [21]. They found that tumors in obese patients had higher expression of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), an increased proportion of plasmacytoid dendritic cells (pDCs) and mast cells and decreased proportion of innate lymphoid cells (NK) compared to tumors in patients with normal weight. It is postulated that the chronically heighted inflammatory status of obese patients may work synergistically with immunotherapy agents. Additionally, leptin levels in obese subjects have been associated with higher T-cell programmed death (PD)-1 expression and improved response to anti-PD-1 therapy [21].

In 2014, it was estimated that worldwide, 640 million adults were obese (a six-fold increase since 1975) and 110 million children and adolescents were obese (a two-fold increase since 1980). In 2013, an estimated 4.5 million deaths worldwide were attributable to conditions related to obesity [22]. The identification of new obesity-related biologic and immunologic alterations associated with cancer sites will add to the number of deaths worldwide attributable to obesity. The obesity paradox is important to the urologist as obesity continues to be a growing problem worldwide and whether causal or correlational, more patients will have concomitant diagnoses of RCC and obesity. A patient’s overall health, including obesity, will continue to be part of treatment conversations and preoperative counseling as obesity can increase postoperative risks, including GCS as discussed in this case.

Conclusions

We present a case of a 38-year-old male with renal mass who underwent robotic-assisted partial nephrectomy and developed GCS in the immediate postoperative period, which was promptly recognized and treated with emergent fasciotomy. For optimal patient outcomes, a high index of suspicion, prompt consultation of surgical specialists and multidisciplinary management, as well as proper preoperative counseling, are crucial.

Acknowledgments

None to declare.

Financial Disclosure

The work was supported by a grant from the National Cancer Institute (No. 2P30CA016058-45).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no potential conflict of interest.

Informed Consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient to present and publish this case report.

Author Contributions

A. Lombardo: writing - original draft preparation, writing - review and editing. D. Evans: writing - original draft preparation. H. Harris: writing - review and editing. D. Li: writing - review and editing. J. Bishop: writing - review and editing. E. A. Singer: conceptualization, writing - review and editing.

Data Availability

The authors declare that data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article.

Abbreviations

ACS: acute compartment syndrome; BMI: body mass index; CSM: cancer-specific mortality; ccRCC: clear cell renal cell carcinoma; CT: computed tomography; CK: creatine kinase; COX-2: cyclooxygenase 2; GCS: gluteal compartment syndrome; ICP: intra-compartmental pressure; LOS: length of stay; MRI: magnetic resonance imaging; mRCC: metastatic renal cell carcinoma; OS: overall survival; PD: programmed death; PFS: progression-free survival; PGE2: prostaglandin E2; ROM: range of motion; RFS: recurrence-free survival; RCC: renal cell carcinoma; WAT: white adipose tissue; WLCS: well leg compartment syndrome

| References | ▴Top |

- Torlincasi AM, Lopez RA, Waseem M. Acute compartment syndrome. In: StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL) ineligible companies. 2025.

pubmed - Miller M, Loebach L, Blachman-Braun R, Nethala D, Millan B, Patel MH, Saini J, et al. Under pressure: a quality improvement initiative to reduce rhabdomyolysis and hospital-acquired pressure injuries after retroperitoneal surgery. Urol Pract. 2025;12(6):717-724.

doi pubmed - Lawrence JE, Cundall-Curry DJ, Stohr KK. Delayed presentation of gluteal compartment syndrome: the argument for fasciotomy. Case Rep Orthop. 2016;2016:9127070.

doi pubmed - Brede CM, Lane BR. Prevention, diagnosis and treatment of rhabdomyolysis after urological surgery. J Urol. 2016;195(2):245-246.

doi pubmed - Gelpi-Hammerschmidt F, Tinay I, Allard CB, Su LM, Preston MA, Trinh QD, Kibel AS, et al. The contemporary incidence and sequelae of rhabdomyolysis following extirpative renal surgery: a population based analysis. J Urol. 2016;195(2):399-405.

doi pubmed - Adib F, Posner AD, O'Hara NN, O'Toole RV. Gluteal compartment syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Injury. 2022;53(3):1209-1217.

doi pubmed - Chatzizisis YS, Misirli G, Hatzitolios AI, Giannoglou GD. The syndrome of rhabdomyolysis: complications and treatment. Eur J Intern Med. 2008;19(8):568-574.

doi pubmed - Yang SS, Anidjar M, Azzam MA. 'A pain in the buttock': A case report of gluteal compartment syndrome after robotic partial nephrectomy. J Perioper Pract. 2023;33(9):263-268.

doi pubmed - Raza A, Byrne D, Townell N. Lower limb (well leg) compartment syndrome after urological pelvic surgery. J Urol. 2004;171(1):5-11.

doi pubmed - Rosevear HM, Lightfoot AJ, Zahs M, Waxman SW, Winfield HN. Lessons learned from a case of calf compartment syndrome after robot-assisted laparoscopic prostatectomy. J Endourol. 2010;24(10):1597-1601.

doi pubmed - Heyn J, Ladurner R, Ozimek A, Vogel T, Hallfeldt KK, Mussack T. Gluteal compartment syndrome after prostatectomy caused by incorrect positioning. Eur J Med Res. 2006;11(4):170-173.

pubmed - Keene R, Froelich JM, Milbrandt JC, Idusuyi OB. Bilateral gluteal compartment syndrome following robotic-assisted prostatectomy. Orthopedics. 2010;33(11):852.

doi pubmed - Li M, Bu R. Biological support to obesity paradox in renal cell carcinoma: a review. Urol Int. 2020;104(11-12):837-848.

doi pubmed - Ji J, Yao Y, Guan F, Luo L, Zhang G. Impact of BMI on the survival of renal cell carcinoma patients treated with targeted therapy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Nutr Cancer. 2023;75(9):1768-1782.

doi pubmed - Santoni M, Massari F, Bracarda S, Procopio G, Milella M, De Giorgi U, Basso U, et al. Body mass index in patients treated with cabozantinib for advanced renal cell carcinoma: a new prognostic factor? Diagnostics (Basel). 2021;11(1):138.

doi pubmed - Takemura K, Yonekura S, Downey LE, Evangelopoulos D, Heng DYC. Impact of body mass index on survival outcomes of patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma in the immuno-oncology era: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Urol Open Sci. 2022;39:62-71.

doi pubmed - Darbas T, Forestier G, Leobon S, Pestre J, Jesus P, Lachatre D, Tubiana-Mathieu N, et al. Impact of body composition in overweight and obese patients with localised renal cell carcinoma. In Vivo. 2020;34(5):2873-2881.

doi pubmed - Saitta C, Afari JA, Walia A, Patil D, Tanaka H, Hakimi K, Wang L, et al. Unraveling the BMI paradox in different renal cortical tumors: insights from the INMARC registry. Urol Oncol. 2024;42(4):119.e1-119.e16.

doi pubmed - Graff RE, Wilson KM, Sanchez A, Chang SL, McDermott DF, Choueiri TK, Cho E, et al. Obesity in relation to renal cell carcinoma incidence and survival in three prospective studies. Eur Urol. 2022;82(3):247-251.

doi pubmed - Huang F, Xu P, Yue Z, Song Y, Hu K, Zhao X, Gao M, et al. Body Weight Correlates with Molecular Variances in Patients with Cancer. Cancer Res. 2024;84(5):757-770.

doi pubmed - Sanchez A, Furberg H, Kuo F, Vuong L, Ged Y, Patil S, Ostrovnaya I, et al. Transcriptomic signatures related to the obesity paradox in patients with clear cell renal cell carcinoma: a cohort study. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21(2):283-293.

doi pubmed - IARC identifies eight additional cancer sites linked to overweight and obesity. East Mediterr Health J. 2016;22(8):641.

pubmed

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (CC BY 4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, including commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited.

World Journal of Nephrology and Urology is published by Elmer Press Inc.